KubeCon Europe 2018 - Memo and Takeaways

CommentsThe KubeCon and CloudNativeConf Europe 2018 is just over and it was really a blast! I had the opportunity to meet and talk with a lot of talented and smart people, share ideas and learn, learn a lot.

Despite the conference and the city are quite expensive for people - like me - coming from the south of Europe, it was really worth the money and my feeling at the end of the conference was more or less this:

A deep sense of sadness hit me tonight. I enjoyed this #KubeCon more than any other conf. Really, it was a blast! I will miss the amazing talented people I've met. From the deep of my hearth, I would like to work with all of you. Kudos, great community.

— Marco 🇪🇺 (@pracucci) May 4, 2018

I’m used to take notes at each conference I attend and KubeCon was not an exception. In this post I will share random notes and takeaways from the conf, in the form of a publicly-shared personal memo. It just covers talks I’ve attended, that means it just covers my personal interests within the wide CNCF landscape.

It’s an opinionated list of notes with inputs from talks and people I’ve met. It doesn’t pretend to be neither discursive, complete or fully accurate. They’re just my notes, as a starting point from which I will deep dive into the next weeks and months.

In this memo:

- Notes on the conference organization

- Notes on autoscaling

- Notes on networking

- Notes on AWS EKS

- Notes on resource management

- Notes on monitoring

- Notes on security

- Notes on tools

- Keynotes really worth to watch

Notes on the conference organization

First of all, a big shout out to CNCF and all people involved in running the conference. Everything was perfect, from the beautiful location to the food catering being able to feed 4300 people without queues, from the evening party at Tivoli Gardens to the high quality keynotes and talks.

Well done!

Notes on autoscaling

Kubernetes support three types of autoscaling:

- Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA)

- Vertical Pod Autoscaler (VPA)

- Cluster Autoscaler (CA)

Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA)

- Scales up/down the number of replicas of a pod.

- Requires gauge metrics.

- Built-in support for CPU and memory pod metrics.

- Works best with stateless applications.

Vertical Pod Autoscaler (VPA)

- Adjust resource requests (CPU and Mem requests) for the containers in a pod, based on usage. Since currently it’s not possible to change container resources without restarting the pod, Kubernetes will restart the pod each time the resources change.

- Can operate in three modes:

Auto: VPA assigns resource requests on pod creation as well as updates them on running pods (default).Initial: VPA only assigns resource requests on pod creation and never changes them later.Off: VPA just calculate the recommended resources - not applying them to the pod - and allow the human operator to inspect them via the VPA object and eventually manually apply them on the pod.

- Controlled by a Custom Resource Definition object called

VerticalPodAutoscalerwhich allow to select the pod to autoscale by labels, set the operating mode and min/max allowed resources. - VPA should be used when HPA is not an option or not appropriate (ie. StatefulSets).

- It’s strongly suggested to not mix VPA and HPA. They both try to solve the same exact problem in a different way, and they conflict if run together on the same pod - unless very special care is taken.

Cluster Autoscaler (CA)

- Adjust the number of nodes in the cluster.

- It’s quite complex since it runs a “simulation” of the pods scheduler in order to determine which nodes pool should be scaled up/down and allows you to set some “extra buffer” to always have some spare resources on the cluster.

- An alternative (simpler) cluster autoscaler for AWS (kube-aws-autoscaler) has been built at Zalando and run it in production for quite a long time, while they now moved to the Kubernetes CA.

What’s about the future?

- In Kubernetes 1.11 the HPA will be able to autoscale based on CRDs, so that it can be used to scale not just pods but custom resources too

- Prediction by Frederic Branczyk: cluster autoscaler will not to be a special case at some point in the future

Horizontal Pod Autoscaling with custom metrics (Prometheus)

Kubernetes 1.8 introduced Resource and Custom Metrics API, as an attempt to decouple the HPA from Heapstep/cAdvisor metrics and allow to autoscale based on custom metrics (ie. Prometheus) or external metrics (outside the cluster).

Resource and Custom Metrics API is not an implementation, but an API specification implemented and maintaned by vendors. The contract of such APIs is that each metric should return a single value upon which the HPA will scale the workload.

Resource Metrics API

- Collects resource metrics (currently CPU and memory).

metrics-serveris the canonical implementation, which collects metrics from thekubeletstats API every minute and holds the state - all values on Pods and Nodes - in memory.

Custom Metrics API

- Allows requesting arbitrary metrics.

- It’s a specification and no canonical implementation is provided. Implementations are specific to the respective backing monitoring system.

- The first monitoring system supported was Prometheus by k8s-prometheus-adapter (an “adapter” is the implementation of the custom metrics API for a specific backing monitoring system).

- Supported Kubernetes objects are

Pod,ServiceorDeployment.

External Metrics API

- Introduced in Kubernetes 1.10 (alpha).

- Allow to autoscale based on metrics not related to any Kubernetes object and coming from outside the Kubernetes cluster (ie. number of jobs in a queue).

- The design is similar to Custom Metrics API and external metrics are ingested via an adapter as well.

Notes on networking

Networking is hard and Kubernetes networking is harder. However, the overall outcome of this KubeCon is that we should stop getting scared about Kubernetes networking and better understand how it works. It’s complicated, but there’s no magic behind it and - with some study and practice - it’s approachable.

Debugging networking issues

In case of a networking issue, the first thing to do is to collect information. Two suggested starting points (in case no overlay network is used):

- Dump the iptables rules with

iptables-save, in order to get a snapshot of the current rules for later analysis (before they change and maybe the issue vanish). - Use

conntrack -Lto list all connections tracked by the Connection Tracking System, which is the module that provides stateful packet inspection for iptables and has a primary role in packets routing.

Slides: Blackholes & Wormholes: Understand and Troubleshoot the “Magic” of k8s Networking

CNI

The CNI (Container Network Interface) is a both a specification document and a set of “base” (common) plugins aiming to abstract the way applications (ie. Kubernetes) add and remove network interfaces on the host. CNI specification is not Kubernetes-specific, while being supported by Kubernetes.

The goal is to provide an interface layer between the application and the host, and a set of interchangeable community/vendor driven plugins that do the real work to attach/detach/configure network interfaces.

The specification is very simple and currently support ADD and REMOVE operations, while a GET is going to be introduced soon. The specification is still a draft, but close to be finalized in the 1.0 version (should be released by the end of 2018) after which the specification will be considered feature freeze, and the whole effort will be put in adding and/or improving plugins.

AWS has developed two CNI plugins:

Pods networking in Kubernetes using AWS Elastic Network Interfaces

The amazon-vpc-cni-k8s plugin allows to setup a Kubernetes cluster where pods networking is based on the VPC native networking using multiple ENIs attached to the EC2 instance. Using this plugin, all pods and all nodes will be addressable in the same VPC network space.

Since the number of ENIs that can be attached to an EC2 instance is limited, the plugin leverage on the ability to add multiple secondary IPs to each ENI in order to increase the number of Pods addressable on each node (the number depends on the instance type).

The plugin reserves 1 IP per ENI for its own purposes, while the remaining ones can be used for Pods networking. For example, a c4.large instance can attach up to 3 interfaces, each can have up to 10 addresses and so the total number of pods schedulable on a c4.large instance using ENI networking is 3 * (10 - 1) = 27 that sounds quite reasonable unless you’ve a bunch of micro pods.

The amazon-vpc-cni-k8s plugin is used in EKS as well. According to Anirudh Aithal (AWS Engineer) it can already be used for production workload despite the official status is still alpha (will be switched to stable once EKS enters GA). I’ve also talked to few people at the conference already using it in production (with no issues).

Slides:

Notes on AWS EKS

I didn’t met anyone having access to EKS (I haven’t been much lucky), despite most of the people I’ve met run Kubernetes on AWS. People running multi cloud says GKE is a step above and works really well: there’s consensus on this.

Key Points:

- EKS is a certified distribution of Kubernetes and will run Kubernetes upstream (no forked / limited version).

- EKS manage Kubernetes masters (HA) and etcd (HA, 3 AZs, encrypted, does backups), while workers must be provisioned and managed by customers.

- Allow to specify the major version (ie.

1.9) while EKS will keep all masters automatically updated to the latest minor (ie. to patch security issues). - Allow to setup manual or automatic major version upgrades.

- Masters and etcd are not directly accessible.

- Masters are automatically vertically scaled (EC2 instance type) based on the number of pods running on the cluster (very cool).

- No customer-provided pods can be scheduled on masters.

- EKS pods scheduling is aware of the maximum number of pods schedulable on each worker node (due to ENI limitation).

Networking:

- EKS setup a public load balancer in front of the API servers (ie.

mycluster.eks.amazonaws.com). Support for internal load balancer is on the roadmap, but will likely be introduced after GA. - Pods networking uses the VPC native networking.

Authentication:

- EKS takes care of certificates management, supporting certificates rotation.

- There’s no AWS-maintained plugin to assign IAM roles to pods. The community driven

kube2iamis the best option available so far, even if not much recommended by AWS (at some point they might work on a solution based on spiffe). kubectlauthentication is based on IAM, using heptio-authenticator-aws. The AWS Identity is only used for thekubectauthentication and - once authenticated - Kubernetes native RBAC is used for the authorization. It requireskubectl1.10+ since support for pluggable authentication providers has been added in this version.

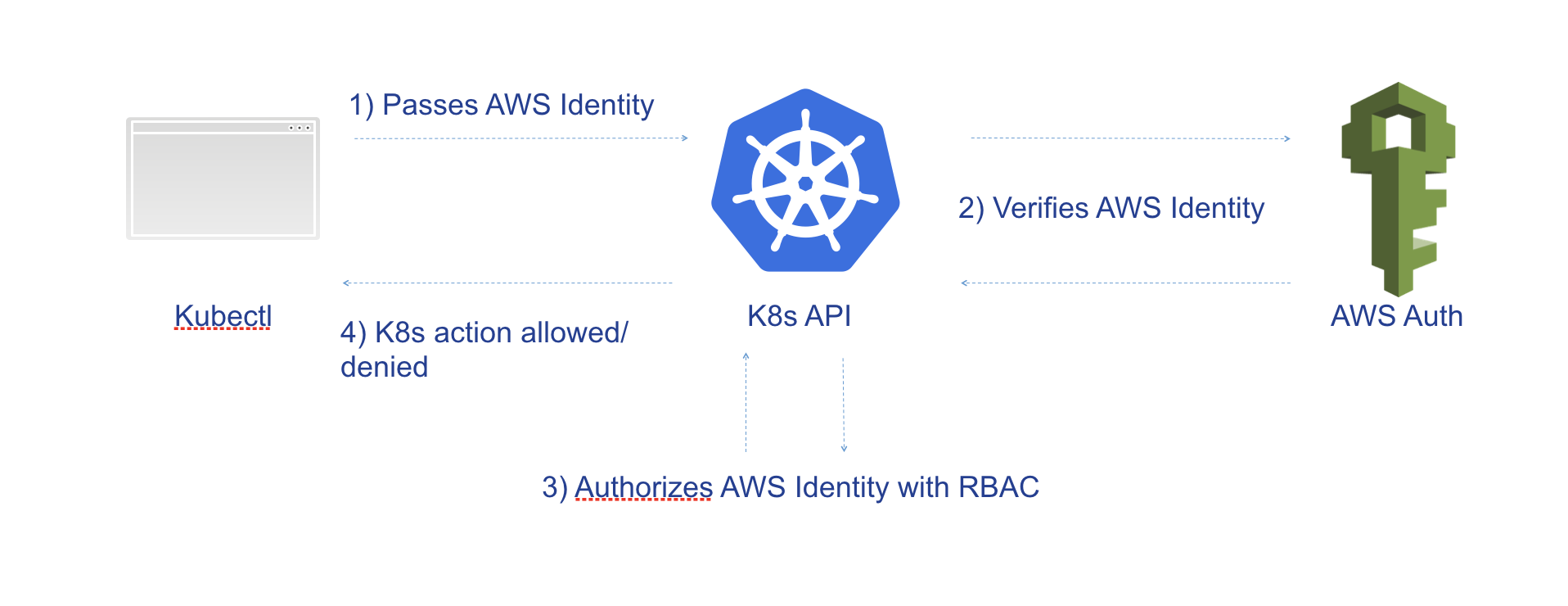

IAM authentication works like this:

kubectlpasses the AWS Identity to K8S API server- The K8S API Server verifies the AWS Identity with the AWS Auth API

- On success, it authorize the AWS Identity with RBAC - starting from this point, IAM not used anymore

Source: Introducing Amazon EKS

Preview vs GA:

- EKS preview is not production ready, do not run production workload.

- EKS preview requires a custom version of

kubectlfor the cluster authentication, while EKS GA will support the streamlinekubectl. - EKS preview requires a pre-configured AMI provided by AWS and created with a Packer script. AWS will opensource the Packer script once EKS will reach GA, so that customers can build their own workers AMI based on the AWS Packer script.

- EKS GA will “destroy” all clusters created in preview, so another good reason to not run production workload.

- EKS GA will be ready by the end of the year (hopefully before).

- Pricing will be announced once GA

What’s about the future?

- Fargate for EKS might be introduced (similar to the currently available Fargate for ECS).

Slides: Introducing Amazon EKS (.pptx)

Notes on resource management

A quick recap on container resources

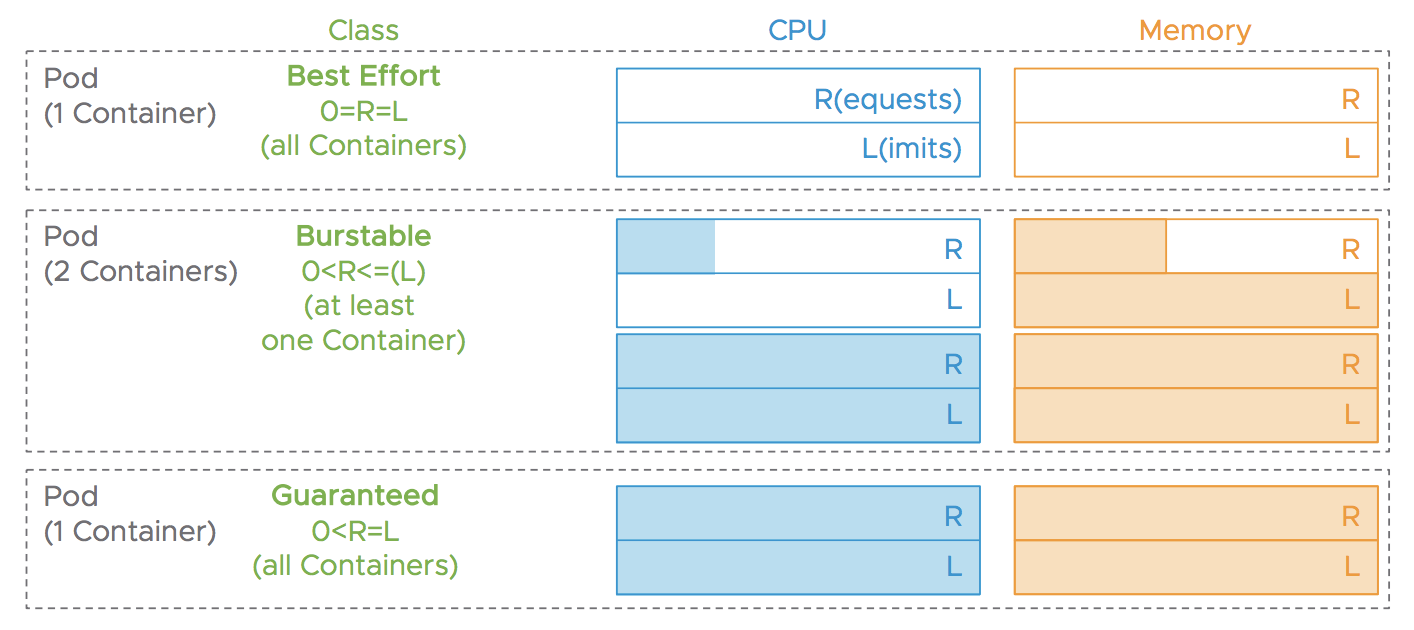

Each container in a pod can specify resource requests and limits (ie. CPU and memory). When a pod has no resource requests / limits, it will run with the Best Effort QoS class which is the most likely to get throttled and evicted.

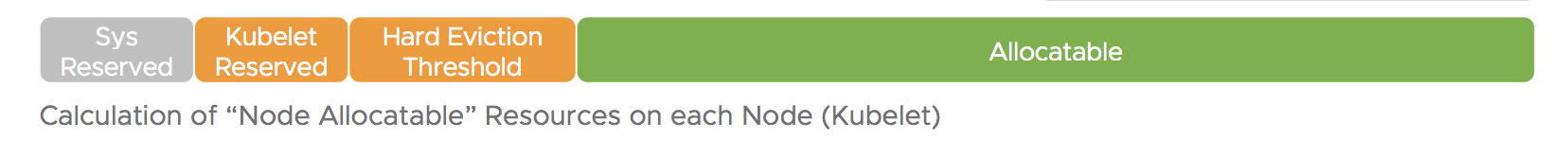

The scheduler keeps track of “allocatable” resources on each node that are tipically lower than its capacity, since some resources are reserved for the system, the kubelet and a buffer for the hard eviction threshold.

You can get a summary of both "Node capacity" and "Node allocatable" resources via `kubectl describe node <name>`, ie.

Capacity:

cpu: 2

memory: 15657244Ki

pods: 110

Allocatable:

cpu: 2

memory: 15554844Ki

pods: 110

When the scheduler algorithm places a pod an a node it doesn’t allow for overcommit of requested resources, so the total sum of requested resources must be <= the allocatable resources. Resource limits are currently not taken into account by the scheduler, despite some initial work has been done (alpha and behind feature gate).

Each pod has a QoS class implicitely assigned based upon its containers CPU and memory resources and limits:

Best Effort: no CPU and memory requests / limitsBurstable: at least one container has CPU and memory requests / limitsGuaranteed: all containers have CPU and memory requests / limits

Each container resource is either compressable (CPU) or uncompressable (memory and storage):

- Compressable: subject to throttling

- Uncompressable: subject to

kubeleteviction or kernel’sOOM_kill

Kubelet eviction policy allows to specify hard and soft thresholds: when a soft threshold is reached a SIGTERM is sent to the container to allow a graceful termination, while in case of hard threshold the container is immediately killed. If the kubelet is not fast enough to react, the kernel’s OOM killer will kill the container.

Known issues

- Some language runtimes (ie. Java, .NET, Go, …) have no or limited cgroups awareness

Java: heap size (a first attempt to solve it has been introduced with-XX:+UnlockExperimentalVMOptions -XX:+UseCGroupMemoryLimitForHeapat some point in Java 8, while Java 10 made big improvements)Go: thread pool size.NET: GC Tuning

Best practices on container resources

- If in doubt, start with

GuaranteedQoS class - Protect critical Pods (ie. DaemonSets, controller, master components, monitoring)

- Apply

BurstableorGuaranteedQoS class with sufficient memory requests - Reserve node resources with labels / selectors, or apply

PriorityClasses(still alpha - hopefully beta in 1.11) if scheduler priority is enabled

- Apply

- Test and/or enforce resources in your CI/CD pipeline

- Monitor container resources usage

- Fine tune the

kubelet--eviction-hardand--eviction-soft(and related Values like Grace Periods)--fail-swap-on(default in recent Versions)--kube-reservedand--system-reservedfor critical System and Kubernetes Services

- Use

BurstableQoS class without CPU limits for performance-critical workloads - Disable swap (required by

kubeletfor proper QoS calculation) - Use the latest version of language runtimes (because of cgroups awareness support improvements) and/or align GC and threads parameters based upon resource requests, using environment variables populated from resource fields, ie:

env:

- name: CPU_REQUEST

valueFrom:

resourceFieldRef:

resource: requests.cpu

- name: MEM_LIMIT

valueFrom:

resourceFieldRef:

resource: limits.memory

Slides: Inside Kubernetes Resource Management (QoS)

Notes on monitoring

Have you ever picked a 3rd party Grafana dashboard, imported into your Grafana installation and all charts are broken due to different labels? Well, to me this happens frequently and I’m glad Tom Wilkie and other people are trying to solve this problem introducing Prometheus mixins.

The core idea behind Prometheus mixins is to provide a way to package together templates for Grafana dashboards and Prometheus alerts related to a specific piece of software (ie. etcd), which get “compiled” into dashboard (JSON) and alerts (YAML) files upon providing a required input configuration (ie. label names). These mixins will also allow to distribute dashboards and alerts along with the code, and not separated from it.

jsonnet (a simple yet powerful extension of JSON) has been picked as the templating language for Prometheus mixins and a package manager for jsonnet - called jsonnet-bundler - built.

They also provide a mixin for Kubernets monitoring based on ksonnet, that’s basically a tool to ease config deployment on Kubernetes based on jsonnet templates. Looks complicated, but once you connect all such pieces together it makes quite sense (if you don’t have a trivial setup).

What’s about the future?

- cAdvisor will be soon deprecated and SIG-instrumentation is working on drafting a specification to replace it with something that is more pluggable

Notes on security

I’m the engineer most far from being a security expert you may find, so here is an attempt to sum up some of things I’ve heard around the topic.

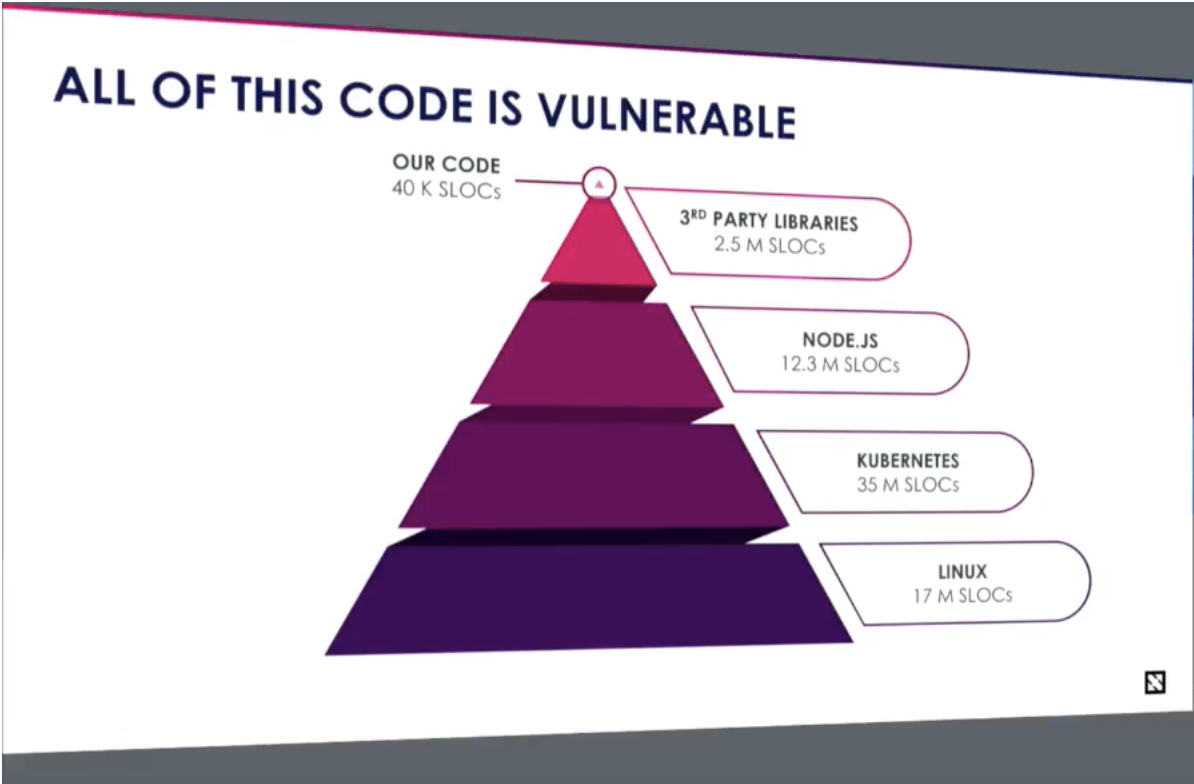

Kubernetes is a complex system with many layers of attack surfaces exposed to internal threats. What we mean by internal threats is any attack driven from inside the container, like when you run untrusted containers on your cluster or an attacker gets access to one of your containers via an external threat.

Internal threats attack surfaces:

- Kernel (attacks via syscalls)

- Storage (ie.

CVE-2017-1002101host-resolved symlinks) - Network (ie.

kubeletAPI server and cloud providers’ metadata service at169.254.169.254) - Daemons (ie. logging)

- Hardware (ie. Spectre v2)

Attacks via kernel syscalls

Run as non root

Configure pods to run as non root:

spec:

securityContext:

runAsUser: 1234

runAsNonRoot: true

And prevent setuid binaries from changing the effective user ID, setting the no_new_privs flag on the container process:

containers:

- name: untrusted-container

securityContext:

allowPrivilegeEscalation: false

Drop capabilities

Historyically Linux had two categories of processes: privileged (run by root) and unprivileged (run by non-root). Privileged processed bypass all kernel permission checks, while unprivileged processed are subject to permission checking based on the process’s credentials (UID, GID).

Starting from Kernel 2.2, Linux introduced capabilities which is a way to split privileges - traditionally associated with root user - into distinct units which can ben independently enabled and disabled on non-root processes (technically they are a per-thread attribute).

By default, Docker has a default list of capabilities that are kept and should be dropped when unnecessary. Default capabilities include but are not limited to:

CAP_SET_UID: Change UIDCAP_NET_BIND_SERVICE: Listen on privileged portsCAP_KILL: Send signals to any processCAP_CHOWN: Change owner of any file

See:

- Docker runtime privilege and default Linux capabilities

- Set capabilities for a Container on Kubernetes

Seccomp

Seccomp limits the system calls a process (container) can make. Vulnerabilites in syscalls that are not allowed won’t hurt anymore. Seccomp profiles in pods can be controlled via annotations on the PodSecurityPolicy (alpha feature).

See: Seccomp on Kubernetes doc

AppArmor

AppArmor is a Linux kernel security module that supplements the standard Linux user and group based permissions to confine programs to a limited set of resources. It basically allows you to define a mandatory access control through profiles tuned to whitelist the access needed by a specific container, such as Linux capabilities, network access, file permissions, etc.

See: AppArmor on Kubernetes doc

Rootless containers

Even if we don’t run containers as root, the system used to run containers (ie. the Docker daemon) still run as root. The talk “The route to rootless containers” illustrates issues and workaround found while running rootless containers.

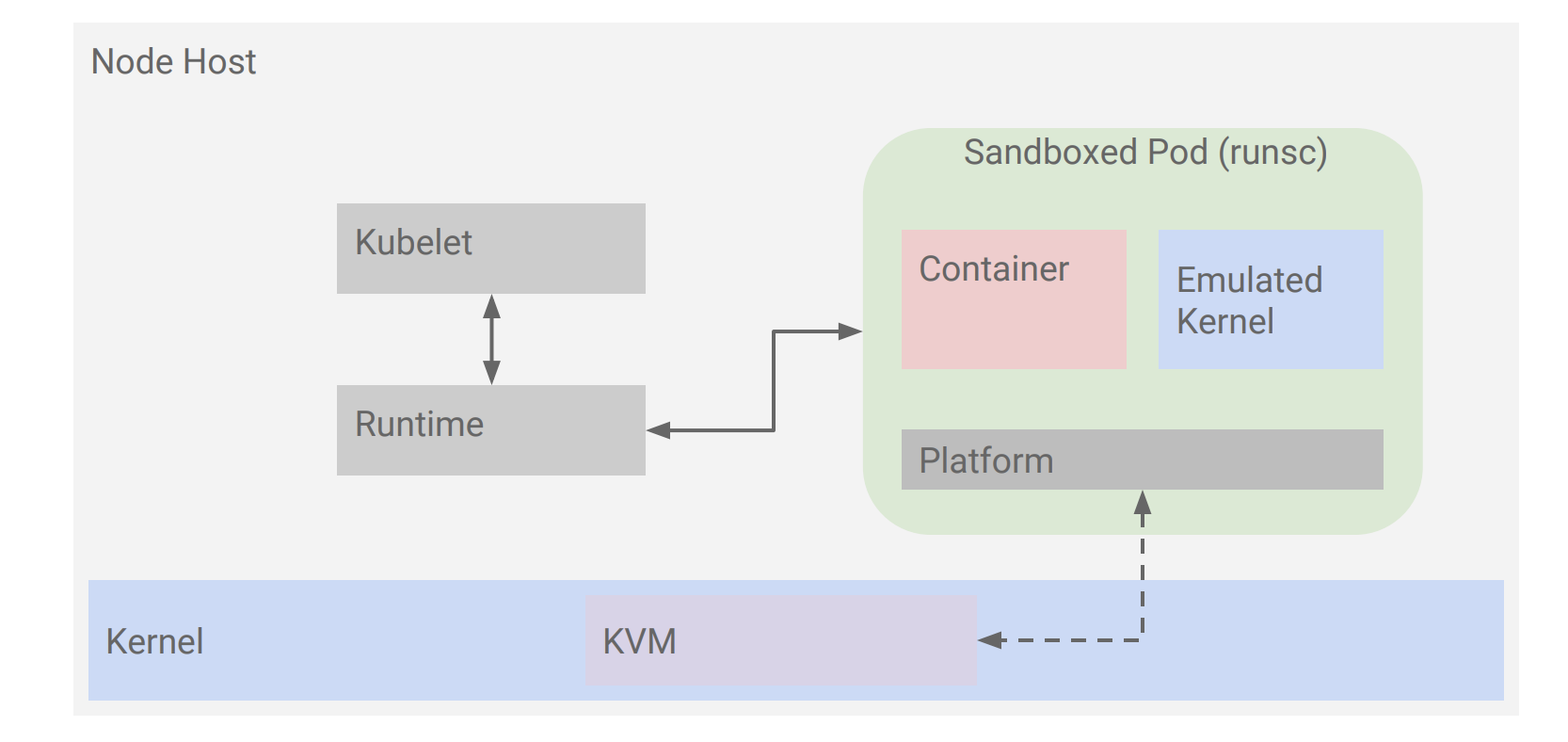

Sandboxed pods

Google has a policy that there should be two distinct defence layers for pods running untrusted code. Given syscalls get directly executed on the host’s kernel, adding a second layer of defence in front of syscalls means running each container on its own (lightweight) kernel, on top of the host’s kernel.

There are two main projects to run sandboxed pods:

- katacontainers (lightweight virtual machines)

- gVisor

gVisor is a user-space kernel - recently opensourced by Google - that implements a substantial portion of the Linux system surface. It includes an OCI runtime called runsc that provides an isolation boundary between the application and the host kernel. The runsc runtime integrates with Docker and Kubernetes, making it simple to run sandboxed containers.

gVisor introduces some performance penalties (working on it), it’s not 100% compatible with runc (ie. some features are not supported due to security reasons) and some work has been left to have a full hardening (ie. networking).

Kubernetes 1.12 will introduce Container Runtime Interface (CRI) API support (alpha) and basic Katacontainers and gVisor implementations - leveraging on CRI - should be expected.

In the future, running sandboxed pods may be as much simple as enabling sandbox in a pod’s security context (API still under discussion):

spec:

securityContext:

sandboxed: true

Slides: Secure Pods

Attacks via system logs

Each container logs to /dev/stdout and /dev/stderr. Such logs are collected by the kubelet and usually processed / parsed by a logging agent (ie. fluentd or logstash) running on the host. Vulnerabilities in logging agents or their dependencies (ie. JSON parser) are not uncommon, and they should be protected as well.

Running the logging agent in a pod (instead of directly on the host), as well as keeping such software updated, and applying the other security best practices is a good starting point to protect from attacks via system logs.

Building Docker images without Docker

The topic is not strictly related to security but is somewhat related when it comes to building Docker images in a secure way from a container running on top of Kubernetes (use cases not limited to this).

The goal around the work people is doing on building Docker images without Docker is to ideally split images building, push/pull and run into different tools.

There are two main approaches:

- Daemon-less

- Runtime-less

Daemon-less

Tools available to build Docker images without running the Docker daemon:

- projectatomic/buildah

- No docker daemon involved

- Can build from

Dockerfile

- genuinetools/img

- No docker daemon involved

- Can build from

Dockerfile - The CLI commands UX are the same as docker build/push/pull/login, so it’s easy to replace existing

dockerintegrations - Uses runc rootless containers (unprivileged on host but not in a container)

Runtime-less

The idea is to get more portable tools not depending on Linux namespaces or cgroups, so that they’re easier to nest inside existing containerized environments:

- GoogleContainerTools/distroless

- No

Dockerfilesupport - Images not based on a distro, but it just packages your application and runtime dependencies (no shell, no package manager), that’s both a pro and a con depending on the use case (but it’s a security best practice)

- It uses

libcinstead ofmusl libccausing larger final images compared to alpine on some circumstances

- No

- GoogleContainerTools/kaniko

- The new kid on the block

- Can build from

Dockerfile - Meant exclusively for running inside containerized environments (ie. Kubernetes)

- Snapshots layer “naively” without union FS (slower)

- No runtime or nested containers

- gVisor (uses a runtime called

runscthat provides an isolation boundary between the application and the host kernel) + kaniko] should be considered the secure way to build untrusted images on a Kubernetes cluster

Slides: Building Docker Images without Docker

Notes on tools

kops

The overall feeling about kops is that it’s still the best tool to provision a Kubernetes cluster on AWS. Every people I talked to use kops in our exact same way (Terraform, no kops cli operations, custom solution to manage rolling updates). Didn’t met anyone using kops rolling updates in production.

The ability to decouple etcd nodes from K8S masters is a feature currently under discussion, but no progress has been made yet. Some people recommend not running etcd on the same masters node, other doesn’t see much issues doing so (I personally see a stronger setup doing the decoupling).

People in favor of splitting etcd from masters, recommends 3+ etcd nodes and 2+ Kubernetes master nodes (scale above two masters only if need to scale up API servers). Moreover the way kops setup the masters is having each API server connecting to the local etcd node (for low latency reasons), that makes this setup potentially more fragile than having a balancer in front of an HA pool of etcd nodes.

k8s-spot-termination-handler by Pusher

DeamonSet deployed on nodes running on AWS Spot instances, that continously watch the AWS metadata service and gracefully drain the node itself when the spot instance receives a termination notice (precisely 2 minutes before it’s termination).

Source: k8s-spot-termination-handler

microscanner by Aqua Security

Free-to-use tool for scanning your container images for package vulnerabilities, based on the same vulnerabilities database of Aqua’s commercial solution. MicroScanner is a binary running during the build steps in a Dockerfile and returns a non-zero exit code (plus a JSON report) if any vulnerability has been found:

ADD https://get.aquasec.com/microscanner /

RUN chmod +x microscanner

RUN microscanner <TOKEN>

A part from adding it directly to the Dockerfile (that’s questionable in my opinion), I personally see it very easy to integrate in a CI/CD pipeline, where on-the-fly Docker images are built FROM the to-be-tested image in a dedicated CI/CD step, microscanner gets executed and its output parsed.

Source: Aqua’s New MicroScanner: Free Image Vulnerability Scanner for Developers

heptio-authenticator-aws by Heptio

A tool for using AWS IAM credentials to authenticate kubectl to a Kubernetes cluster. Requires kubectl 1.10+.

Source:

Kubervisor by AmadeusITGroup

Kubervisor is an operator that control which pods should receive ingress traffic or not based on anomaly detection.

The anomaly detection is based on an analysis done on custom metrics (supports Prometheus) and decisions are taken at the controller level (not on each single pod independently) so that the controller can avoid major distruptions in case the majority of pods are detected as unhealthy (this controller removes traffic from pods only if a minority of them are unhealthy). The query and threshold configuration is up to the user, and can be driven by technical and/or business requirements.

It’s worth to note that the only “write” action done by kubevisor is relabelling pods so that an opportunely configured Service won’t match the unhealthy pod labels and thus will remove traffic from it.

Ie. by default each pod has kubervisor/traffic=yes label and this label matching is added to the Service; unhealthy pods will be relabeled to kubervisor/traffic=no, causing the Service to unmatch the unhealthy pods and get them removed from the pool of available pods.

It’s not used in production yet.

Source:

Operator Framework

CoreOs (now Red Hat) has recently announced the operator-framework, a Go lang framework to ease building operators (or controllers - they’re the same thing, just a different naming).

Keynotes really worth to watch

Most keynotes have been very interesting, but here I’ve shared a couple that - in some way - have inspired me. You can watch all KubeCon / CloudNativeCon videos (keynotes and talks) in this YouTube playlist.

Switching Horses Midstream: The Challenges of Migrating 150+ Microservices to Kubernetes

Anatomy of a Production Kubernetes Outage

How an hour and a half outage root cause started two weeks before, and why having the Kubernetes cluster fully down for such a long period wasn’t a catastrofic failure for a bank. Good lesson on distributed system complexity, post mortem analysis and design for failure.

You may also be interested in ...

- Leveraging Open Source to Improve Cortex and Thanos

- Grafana Loki: like Prometheus, but for Logs

- Migrating to Prometheus: what we learned running it in production (the video)

- Migrating to Prometheus: what we learned running it in production

- Rounding values in Prometheus alerts annotations

- KubeCon 2017 - Prometheus Takeaways

- Prometheus: understanding the delays on alerting

- Install Spark JobServer on AWS EMR

- Linux TCP_RTO_MIN, TCP_RTO_MAX and the tcp_retries2 sysctl

Upcoming conferences

| Incontro DevOps 2020 |

Virtual

Virtual

|

22 October 2020 |

|---|